The paths of life are numerous, only loosely held by our circumstances. Equally, from the opposite side, humans' time on earth is long and it is completely up to them how to allocate it. The problem with time, however, is 1- it passes 2-it ends 3-it is irrecoverable 4-the outcome of whatever you spend your time on is uncertain. Put in other words, time is the ultimate measure of optionality. As such conditions exist, I propose we think of our existence as a portfolio of years.

In the practice of investment management, the main benefit of diversification is to hedge away risks that arise from any one asset. Naturally, this comes at the direct cost of accepting lower returns from that asset as it will constitute a lower percentage of one’s portfolio. And here lies the interesting part.

As a start, for those unfamiliar with the market, an investment portfolio would typically look something like this (oversimplified) :

Graph 1: Investment Portfolio

*This assumes such broker exists where you can actually trade all of these asset classes in one platform

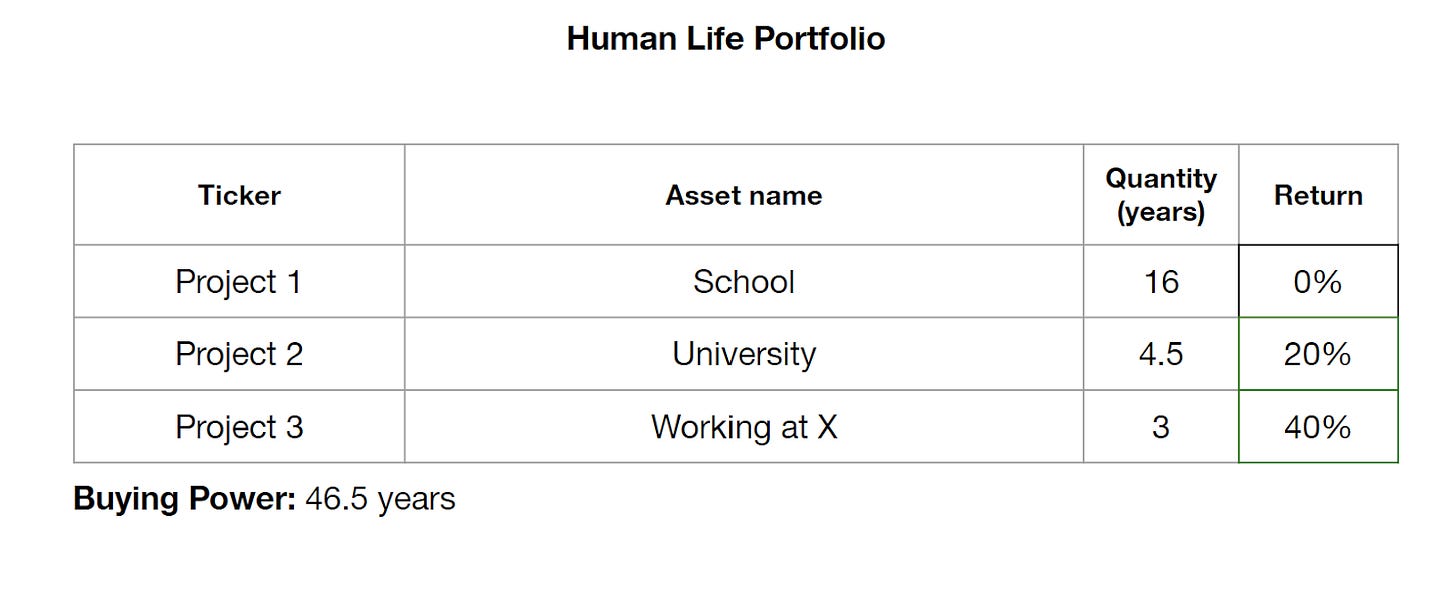

By the same token, a portfolio-ized version of life will look something like this:

Graph 2: Human Life Portfolio

*buying power assumes person will live till the age of 70, thus theoretically the person has 46.5 “years” to spend

Despite the similarity in appearances there are two very important differences between the “portfolios”:

Buying power in life (i.e. time) is on continuous decline even if we don’t consciously allocate it, unlike cash in the investment portfolio

Cash is homogeneous, if you have 1000 SAR the first 1 SAR is exactly the same as the last 1 SAR. That’s not the case for years in our lives however.

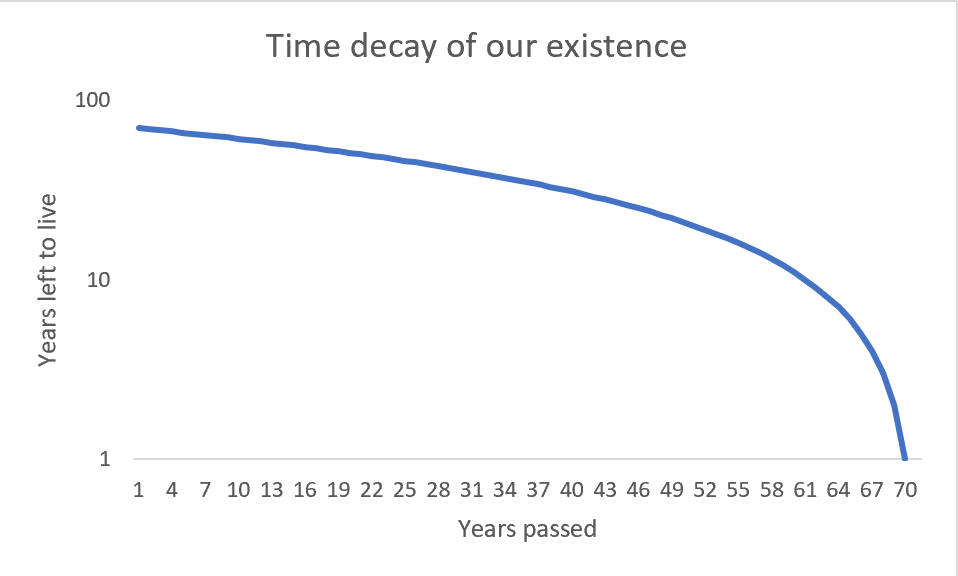

Following on the same thread, the main dynamic in our aging process is how many years we have left to live. When viewed from those lenses, we discover that we are on an exponentially downward slope from the moment we were born (i.e. the rate of decline in how many years we have left to live increases exponentially).

Graph 3: Time Decay

This has all kinds of interesting implications. Perhaps the most clear is that the value of 1 year differs widely depending on when you go through it. A year in your 20’s has much less value than a year in your 90’s. Assuming value is the weight of year x from the years you have left to live, this will look something like this:

Graph 4: Value of 1 year at age x

Another, more pronounced insight can also be arrived at with this framework. It might seem a little bit counterintuitive so let’s take an example first. A person with 40 years to live can spend each year exploring something different, while someone with 1 minute left can only focus on a few things. The normal perception about how this looks like is something like this:

Graph 5: Equal-weighted view of life

What this view acutely misses is the correct weighting of years and how it affects the portfolio construction process. Revisiting the portfolio tables from above, a more realistic investment portfolio will be something similar to this:

Graph 6: Investment Portfolio with positions value

By adding the value of each position we get a more meaningful understanding of the portfolio as a whole. For example it is clear that in this portfolio any outcome for Apple is 5x more important than what happens to Bitcoin. That a 3% gain in Bitcoin cannot offset a 10% loss in Saudi Basic Industries Corporation. Or that cash (buying power) makes up 10% of the portfolio and it can be utilized however the portfolio’s owner sees fit.

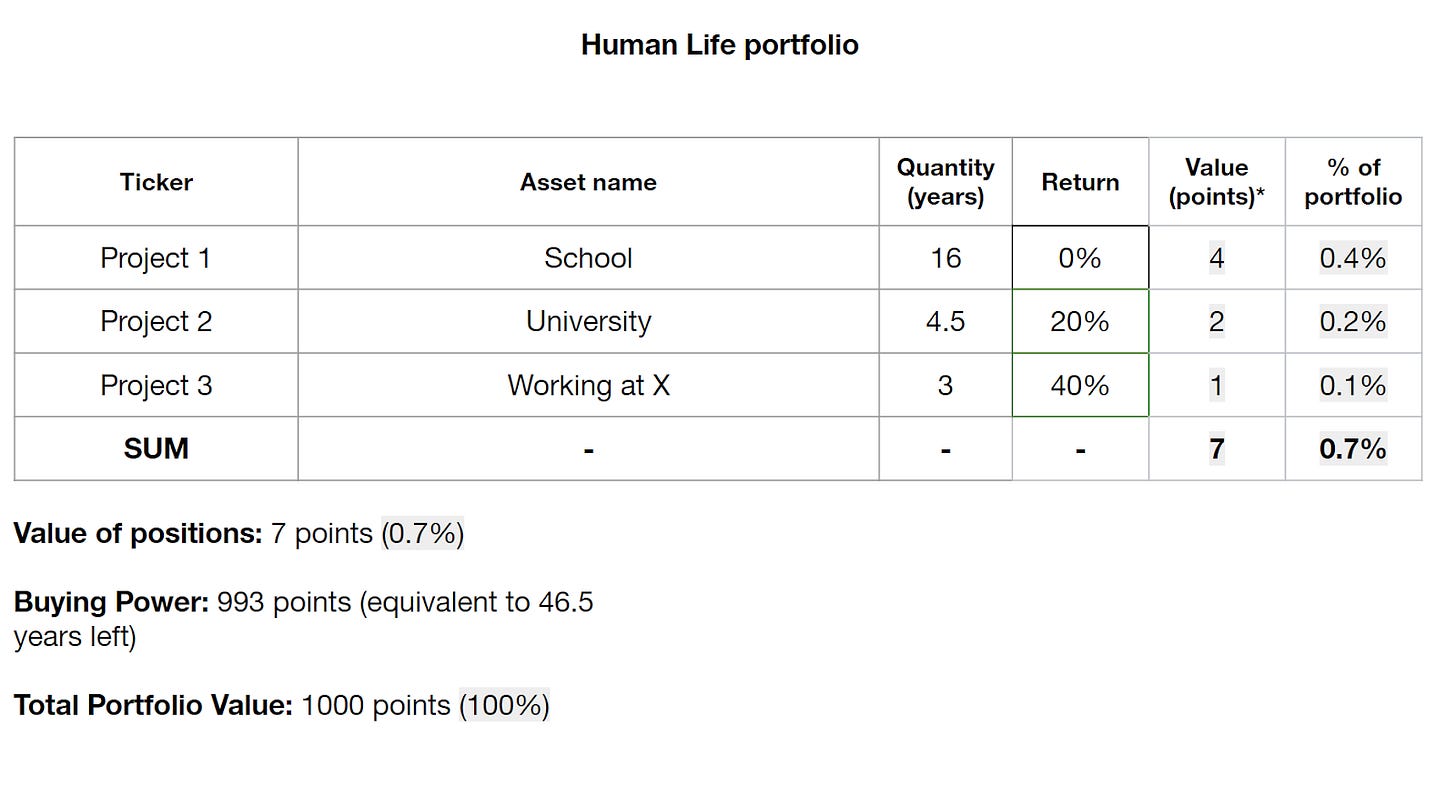

Applying the same concept on the portfolio-ized version of life, a possible interpretation will look something like this:

Graph 7: Human Life Portfolio with positions value

*points are as defined in Graph 4 “Value of 1 year at age x”. Returns were not factored in for the sake of simplicity

What will definitely be striking is the value (and weight) of all the years spent so far by this hypothetical 20-something years old person.

At the face value, it will not appear reasonable, but the basic idea is simple. Mathematically, a 1 year when you have 70 more to live makes a much lower percentage than 1 year when you have 5 to live. More amusingly, however, is what this means for portfolio building. As the weight of years early in life is low, any concentrated bet you make is actually pretty diversified and de-risked. This leaves you with all the upside to gain from such aggressive allocations. Conversely, what you do later in life has a progressively increasing outsized value no matter how much you try to hedge it.

To close off, I’ll leave you with the following food for thoughts. As markets share a lot of the uncertainty and complexity found in real life, here are interesting analogies that are applicable in both:

You can’t control the market but you can position yourself for your best guess on what will happen

No one can consistently beat the market

Timing and trends are everything, seasonality also abounds in both

From time to time the story changes, make sure you are not stuck

Long term works, short term also works (though only for a very small minority with incredible skills and resources)

Thank You.

👌🏻

Big like